All psychological processes invariably take place within a biological body that moves and acts in a physical environment. The acknowledgment of this fact lies at the heart of recent approaches to understanding cognition that emphasize its embodied and situated nature. Rather than thinking of the environment as merely the background in which an individual thinks and acts, we instead seek to understand how the individual and the environment constitute an inseparable, unitary system. James Gibson’s ecological concept of an environment’s affordances, which are defined as the relational, behavioral opportunities that an environment offers a particular perceiver, captures this idea. For example, a chair may afford sitting to an average-sized human, but it also affords climbing, reclining, or hiding-under for a cat. Perceivers must be attuned to this action-oriented information because it is through an awareness of the environment’s possibilities that organisms are actually able to survive within them.

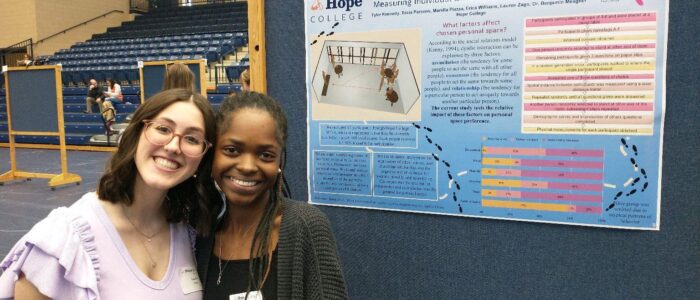

These principles can be applied not just to how we think about particular objects, but also to entire physical settings. As an illustration, the office layouts shown here offer quite different behavioral opportunities to the people within them. One is designed to afford social interaction, whereas the other is designed to afford individual seclusion. My research seeks to understand how people’s experience and awareness of these affordances depends on their relative fit within that environment. Occupants may differ in terms of their social motivations (e.g., being recently rejected), or in terms of their personality (e.g., being high in extraversion or agreeableness), or in terms of their relationship with the other occupants (e.g., being friends or enemies). These factors have the potential to guide people’s perceptual activity within these environments, impacting outcomes such as preference, judgments of space and distance, and the detection of behavioral opportunities.

These principles can be applied not just to how we think about particular objects, but also to entire physical settings. As an illustration, the office layouts shown here offer quite different behavioral opportunities to the people within them. One is designed to afford social interaction, whereas the other is designed to afford individual seclusion. My research seeks to understand how people’s experience and awareness of these affordances depends on their relative fit within that environment. Occupants may differ in terms of their social motivations (e.g., being recently rejected), or in terms of their personality (e.g., being high in extraversion or agreeableness), or in terms of their relationship with the other occupants (e.g., being friends or enemies). These factors have the potential to guide people’s perceptual activity within these environments, impacting outcomes such as preference, judgments of space and distance, and the detection of behavioral opportunities.

Beyond simply being the target of perception, the physical world also plays an active role in guiding and constraining the behaviors that we can engage in. Particular places—such as one’s home, or certain spiritually meaningful settings—can be a psychological resource for supporting adaptive functioning, coping, and emotional well-being. Additionally, our relationship with certain places imbue us with particular roles, such as a host or a visitor, that can have a meaningful impact on social behavior and impression formation. Other places represent the unique context for particular types of social relationships or interactions (e.g., a “work friend”), providing geographic constraints on interpersonal intimacy and friendship. In these (and many other) ways, the physical environment is closely intertwined with our social lives!

Current Projects

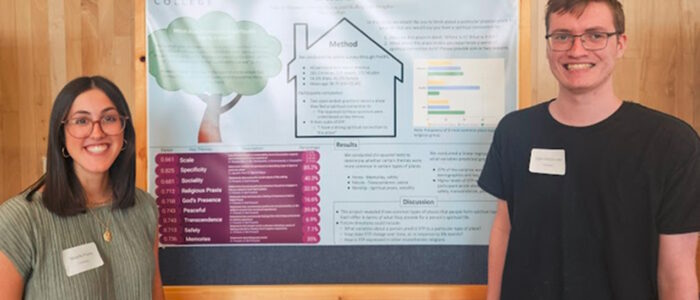

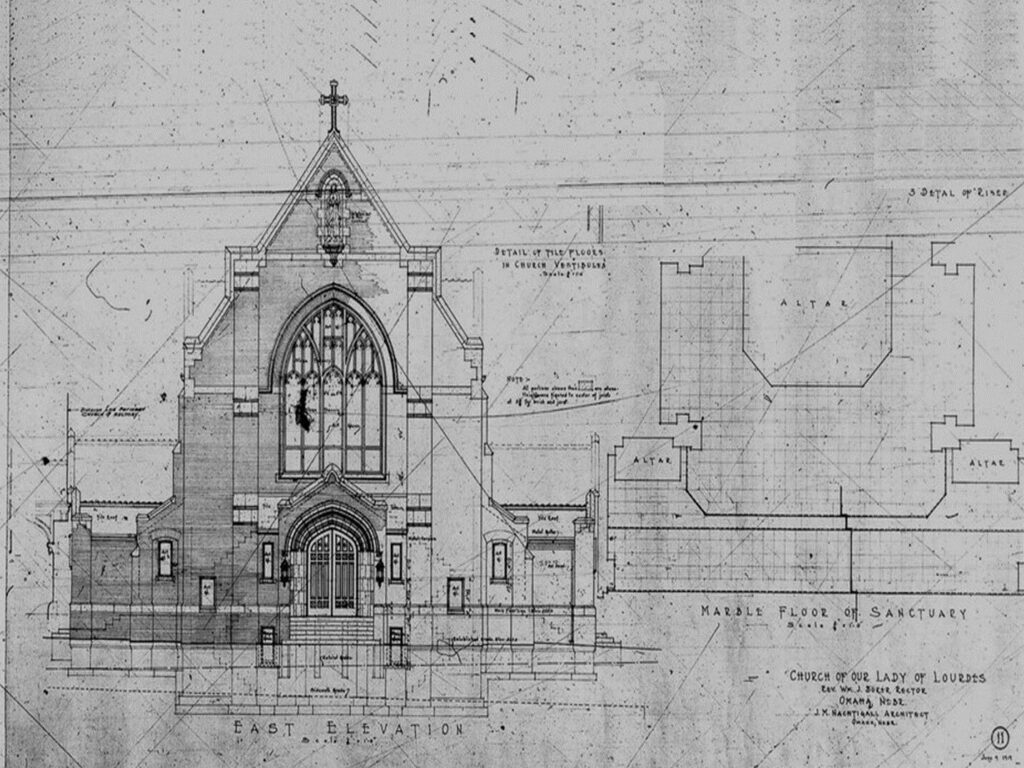

Religious Beliefs and Worship spaces

Certain places in the world feel sacred. But what explains our spiritual connection to these settings? And what are the psychological consequences of being in these spiritually meaningful locations? We are exploring how people’s beliefs about God attune them to certain features of a place, and how the fit between spiritual beliefs and motives and the design of worship spaces can impact people’s emotional experiences.

Interpersonal Hospitality & Hosting

Although homes are sometimes thought of as a refuge from the broader world, people regularly have guests in their territories. In fact, hospitality has long be viewed as an essential virtue across numerous cultural and faith traditions. But what motivates this behavior? And how does interacting with others in the home differ qualitatively from other types of social encounters? We are investigating whether there may be unique benefits to friendship that come from this behavior.

The geography of close relationships

The design of social settings constrains the types of interactions that are possible. As a consequence, places vary in terms of how well they afford each of the wide variety of behaviors that friendships entail (e.g., intimate self-disclosure, shared physical activities, parallel play). We are studying whether certain types of young adult friendships co-occur with their frequency of interacting in certain types of settings on campus.